A new wave of “Man-in-the-Middle” (MitM) attacks is targeting online banking and social media users, affecting customers of over 70 financial institutions.

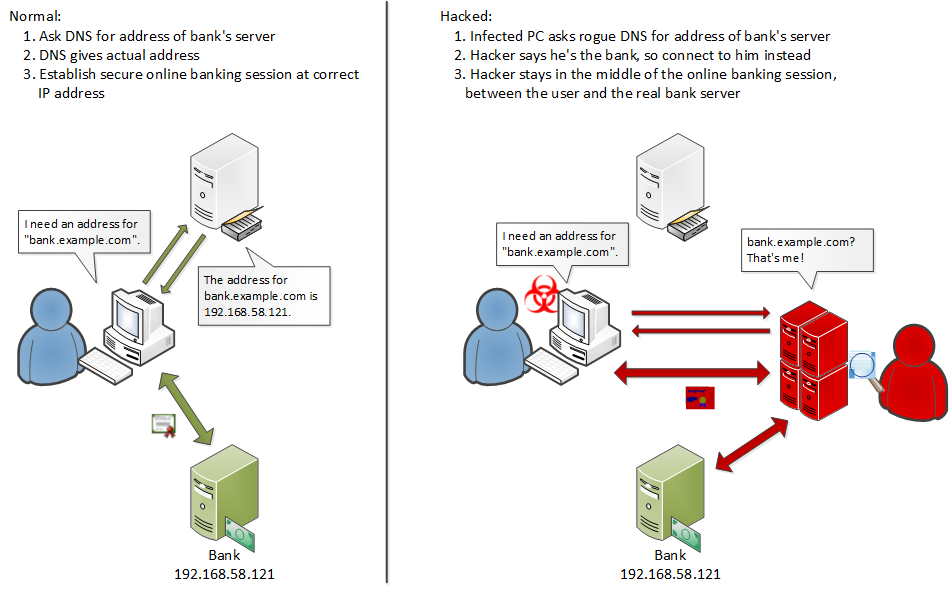

In these attacks, hackers use spam to deliver malware that modifies DNS settings and installs a rogue Certificate Authority (CA). The DNS changes redirect users to the attacker’s DNS servers, which in turn route traffic through malicious proxy servers. Because the rogue CA is trusted by the user’s PC, browsers display the correct website address and the usual security icons, leaving users unaware that an attack is underway.

The attacker’s proxy sits between the user and the legitimate website, capturing login credentials and injecting malicious code into the browsing session, effectively compromising sensitive accounts without triggering any alerts.

Figure 1: Comparison of normal banking session (left) to hacked session (right)

Attack Delivery

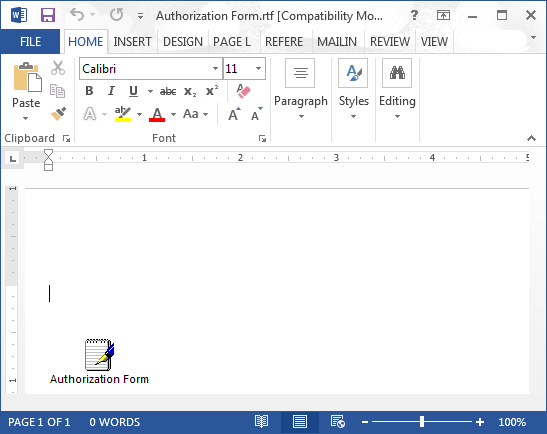

The hacker initiates these attacks by using spam to deliver malware to victims via malicious attachments. In the cases observed by PhishLabs, these spam emails contain a message designed to entice the user to open an attached RTF (Rich Text Format) document. The document contains an OLE (Object Linking and Embedding) object which is actually an executable program file. This program is the malware which changes the DNS and Certificate Authority settings that allow the attack to be performed without any outward signs visible to the user.

Figure 2: EXE file disguised as a RTF document

On many systems, double-clicking an embedded program will execute it. Cybercriminals may use tools to create specially crafted RTF document files that display a familiar data file icon and a caption in most popular word processing programs; thus, hiding or obscuring clues to the executable nature of the object, such as the EXE filename extension.

The Malware

The malware embedded in the spammed documents is a backdoor RAT (Remote Administration Tool) with an initial payload containing instructions to change DNS and security settings when initialized. The file is a Win32 PE (Portable Executable) EXE file and is actually a compiled form of an AutoIt script. The AutoIt scripting tools used offer the option to obfuscate the compiled code, and the version used to produce this malware makes it more difficult to decompile or reverse engineer the resulting EXE file than earlier versions. Some but not all of the samples found have been run through a second "cryptor" to aid in evading detection by anti-malware tools.

Changes to DNS

One of the first actions performed by the malware is changing the DNS settings on the infected user's PC. The malware configures the PC to use the hacker's rogue DNS server to look up names like "www.example.com" and translate them to a numeric network address that is used to locate and connect to the remote system. For domain names of certain targeted websites, the hacker's DNS server is configured to give the infected PC a bogus IP address that points to a proxy server impersonating the actual website being targeted. This causes the user to connect to a system that the hacker can use to spy on and manipulate sensitive data intended for a legitimate website.

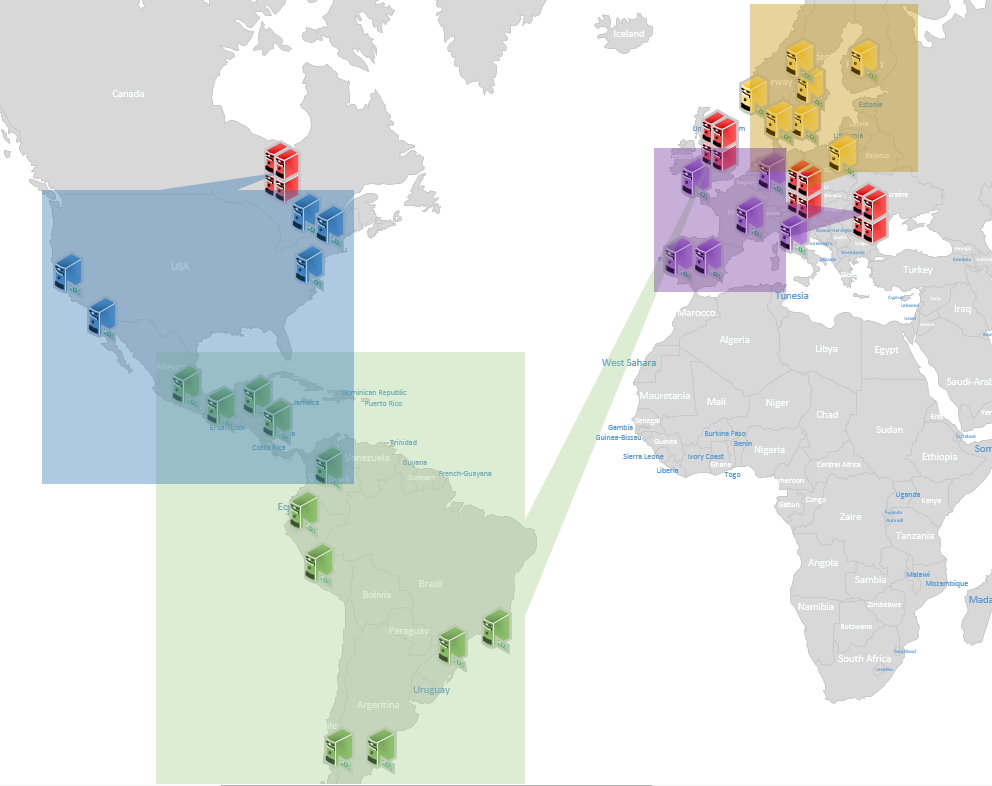

Multiple DNS and proxy servers have been observed being used in these attacks, typically one each per geographic region. For example, the infected PCs of online banking users in South America would be configured to use one DNS server, while those in Western Europe are configured to use another.

The attacker's DNS servers run the BIND nameserver software, and the attackers appear to remotely configure their DNS servers via the rndc utility on port 953/tcp.

Faked Security Credentials

The second essential change made by the malware is the installation of a root certificate for a rogue CA. Once installed, practically everything that uses certificates signed by the rogue CA, such as secured website connections, is trusted implicitly by the infected user's system. The user will not be alerted by any certificate error warnings.

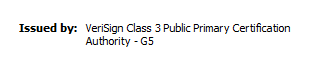

Figure 3: Bogus certificate issuer identity

Certificates used in these attacks impersonate a well-known and widely trusted CA, but this information is controlled by the hacker who generates the certificate; this field could contain anything that the hacker wishes. However, the actual digital signature is not forged and does not match the identity of the legitimate CA.

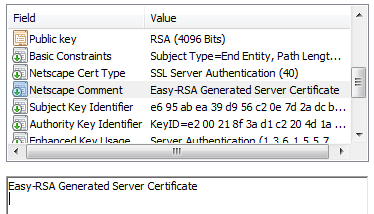

Figure 4: Comment field indicating certificate was generated using "easy-rsa"

A closer look at the certificate information reveals that the certificate was generated using "Easy-RSA" (also known as "easy-rsa" with all lowercase letters), which is a set of scripts previously distributed along with the free OpenSSL utilities that allow users to generate certificates. The easy-rsa tools were designed to make it easy for inexperienced users to create self-signed certificates, using their own private version of a CA. The data in this field is generally not provided by the user, and it's a bit more difficult to modify from the default. In fact, certificates issued by the legitimate CA impersonated in these attacks do not even contain this optional "Netscape Comment" field.

Impersonating Targets

With DNS settings altered and a rogue CA trusted, attackers can seamlessly impersonate secure connections to legitimate websites using a proxy server. The attack typically unfolds as follows:

The victim clicks a link, selects a bookmark, or manually enters a web address (for example,

https://banking.example.com) into the browser.The victim’s computer queries the attacker-controlled DNS server for the IP address of the site.

Instead of returning the bank’s legitimate IP address, the rogue DNS server responds with the IP address of the attacker’s server.

The victim’s computer connects to the attacker’s server and unknowingly begins an online banking session.

The attacker’s server operates as a proxy, relaying requests to the real bank and returning responses to the victim, while silently intercepting data along the way.

From the attacker’s position as the “man in the middle,” complete visibility into the session allows not only the interception of data exchanged between the victim and the bank, but also active manipulation of that information. Warnings can be suppressed, additional authentication details requested, accounts locked, or even unauthorized transactions initiated—all without the user’s knowledge.

From the user’s perspective, everything appears legitimate. The bank’s name displays correctly, security indicators are present, and the session looks no different from a routine online banking interaction.

From the bank’s perspective, the activity also appears largely normal. The attacker’s proxy transparently passes fingerprinting data and cookies between the victim’s browser and the bank’s servers, producing expected and valid results.

In most cases, the only potential anomaly is the source IP address, which reflects the proxy server rather than the victim’s actual device. Relying on this signal alone is impractical, as IP addresses change frequently and users often log in from multiple locations. Effective detection and fraud prevention therefore depend on identifying the malicious proxy infrastructure itself and incorporating those IP addresses into blocklists—making threat intelligence a critical component of defense.

Monitoring Clandestine DNS/Proxy Servers

Both the name servers and proxy web servers involved were purpose-built for these attacks, rather than legitimate systems that had been compromised and reused by the attacker.

Across all observed cases, DNS services — including the rndc service — and web proxy services operated on the same server and shared a single IP address. None of the attacks leveraged separate infrastructure for DNS and proxy functions. The servers were hosted within UK networks and across Central and Eastern Europe. Because victims were not intentionally routed to infrastructure in their own geographic regions, geolocation-based detection of suspicious IP addresses may offer a viable signal for fraud and abuse prevention at some financial institutions.

Figure 5: Rogue DNS/proxy servers (red) handle domains for targets in each general area

Four rogue DNS and proxy servers have been identified, along with the specific target groups associated with each. In total, more than 70 financial institutions were actively targeted. In addition, the servers were configured to proxy traffic for over 25 other websites, enabling the theft of credentials tied to email, social media, and other high‑value accounts.